They also happen to be hallmark signs of many dementias, including the two most common forms: Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.

The undeniable connection between these depression and dementia has ignited a firestorm of research in recent years. Much of the scientific debate centers on a quintessential chicken and egg dilemma—which comes first: depression, or dementia?

Can being diagnosed with dementia cause someone to become depressed, or is depression a harbinger of cognitive impairment to come?

Examining the relationship between dementia and depression

Several new studies aimed at illuminating the relationship between these two cognitive conditions has shed some interesting light on how depression might affect a person's risk for exhibiting signs of dementia later on in life.

A bout of depression may potentially triple a person's risk for developing dementia, according to research recently published in the Archives of General Psychiatry.

Scientists from the University of California, San Francisco, found a significant link between depression and the two most common forms of dementia—Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. The timing of the onset of depression (mid-life versus late-in-life) appeared to have an impact on which type of dementia an individual was more likely to get.

An individual who struggled with depression in their 40s and 50s, was found to be three times more likely than a person without mid-life depression to develop dementia—specifically vascular dementia, which is caused by brain damage due to disrupted blood flow—in their later years.

If, however, an individual became clinically depressed in their 80s and beyond, they were twice as likely as their non-depressed peers to develop Alzheimer's dementia.

A separate study, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, showed similar results, with a slightly different slant.

In their investigation, University of Pittsburgh researchers concluded that late-life depression did indeed increase an individual's risk for acquiring dementia. However it was vascular dementia—not Alzheimer's—that appeared to be most prevalent in depressed older adults.

Causes both biological and behavioral

When asked to explain the mechanisms behind the depression-dementia link, experts extoll a variety of theories.

According to Kenneth Freundlich, Ph.D., a clinical neurologist with the Morris Psychological Group, there are currently several different biological factors that may help explain the relationship between depression and dementia:

- Confusing cortisol: Depressed individuals tend to produce higher amounts of the hormone cortisol, which can impair the areas of the brain that are responsible for short-term memory and learning.

- Disorienting inflammation: Depression can also cause blood vessel-damaging inflammation to occur in the brain.

- Stress-induced damage: The hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for turning information into memory, can be harmed when exposed to extended periods of stress.

"Despite a variety of theories, the depression-dementia link is one that is not fully understood," he says, "People who are experiencing the early stages of dementia frequently become depressed and people who are depressed have an increased risk for developing dementia."

There are also certain behavioral elements which may play a role, according to Robin Dessel, Director of Memory Care at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale. Dessel says, "Depression and dementia mirror each other in a catalogue of symptoms and triggers. There is a very real and integral connection between the health and well-being of brain and body, mind and spirit."

For example, one of the primary symptoms of depression is an unwillingness to engage in regular activities and socialization opportunities, which may lead to what Dessel refers to as an, "inactive brain and a depressed lifestyle."

This lack of action can enhance an individual's susceptibility to showing signs of dementia, especially when compounded by certain genetic, physiological and environmental factors that have been shown to contribute to cognitive impairment.

Identifying and managing depression while caregiving

The specific factors that underlie the depression-dementia link are still foggy. However, the need to effectively identify and treat depression in adults—regardless of their age—is crystal clear.

Nearly 19 million American adults suffer from depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control. More than one-third of these individuals are over age 65. Depression is not a symptom of aging; it is a legitimate psychological condition that requires intervention.

Caregivers need to be ultra-vigilant and on-the-lookout for the warning signs of depression, both in themselves and in their elderly loved ones. Common symptoms of depression include:

- Feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness or helplessness

- Excessive worrying

- Trouble sleeping or concentrating

- Becoming socially withdrawn

- Thoughts of suicide

Once a diagnosis has been made, there are specific steps that can be taken to help someone who suffers from depression.

_____________________________________

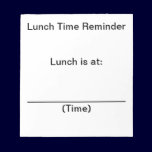

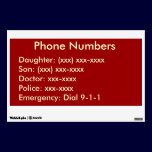

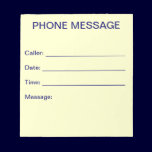

Reminder Notes and Memory Aids

$26.50 - Weekly To Do List Notepad

see on 2 styles

No comments:

Post a Comment